A small trench was excavated in the least disturbed area of the floor to investigate the depth of the foundations of the newly revealed walls, and the make up of the flint packed surface. Ceramics of a similar date to the clearance rubble were excavated mixed in with more CBM, glass, some small fragments of coal and in addition pieces of bone, oyster shell and some clay pipe stems. Three abraded sherds of an earlier date were also excavated. A clay lined feature was exposed containing a 23 cm length of vertebrae (provisionally identified as sheep). The feature underlies the foundation of the walls and the section of vertebrae also appears to continue beneath the wall.

Further investigation of the animal bones and ceramics is ongoing, and we shall probably return to the site in the future.

The photos below show the disturbed area and exposed wall foundations; the foundation of newly exposed wall and the clay feature with vertebrae; the pottery from an earlier date.

August 2023: Little Missenden Dig

In August 2023, CVAHS followed up on our geophysics survey of April 2022 to investigate a potential Romano-British site. As previously reported in Latest News, geophysics had shown promising features beneath the surface of a paddock near the church, and the church is known to include Roman bricks in its structure.

We opened two trenches:

In Trench 1 we had a promising start, where a man-made surface was uncovered about 8cm below the turf. Above this surface we found a variety of tiles, pottery, glass and ceramics, but nothing that was easily identifiable. One interesting find was a piece of school slate and part of a stylus, possibly related to the nearby primary school which was founded in the 1880s.

The surface consisted of a tight compaction of flint cobbles and tile fragments, with an uneven top surface, suggesting a made surface within a building rather than an outside courtyard. A thin layer of sandy subsoil can be seen in the profile above the surface suggesting that it was probably levelled with a sandy floor to make it more even and comfortable underfoot. Unfortunately, we didn’t have an opportunity to seek out an edge. There is no indication as to the type of building associated with the floor surface, but in all probability it belonged to a barn or a stable, rather than a dwelling. The incorporated building material is of uncertain age, but the structure must predate the earliest 19th century maps.

Nothing man-made was found beneath the floor surface, simply large flints, river gravel and sand. Our hypothesis is that the this layer was laid down by the retreating glaciers at the end of the last ice-age, followed by flooding from the Misbourne river depositing, gravel, sand and small pebbles. No clay was found in the area, which is in keeping with records held by the British Geological Society survey.

Trench 2 yielded similar finds to Trench 1, but we didn’t find a man-made surface.

Unfortunately, none of the finds appeared to be of Romano-British origin. The fragments of pottery found were either glazed on both sides or on one side only, and probably of medieval and post medieval dates.

Owing to the terms of agreement with the land owner, CVAHS is unable at this time to continue with the excavation. It is hoped that new arrangements will be negotiated to continue the excavation in the future.

The photos below show a birdseye view if the site; assorted ceramic finds; the base of Trench 1.

May 2022: Time Team, Then and Now

For those of you who haven’t heard the good news, Time Team is back. The new crowd-funded production is now available on YouTube and initially covers two digs – an Iron Age complex of underground tunnels, and the site of a suspected Roman villa.

Each dig is covered in three half-hour programmes, one for each of the dig days, so the pace is a bit less hectic than the original series. Some of the original experts return, plus some new faces, and the familiar title sequence, music and logo give it a nice feeling of continuity. See https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCDvcavTI2xgfXZdF9MaPKIQ

And for those who’d like to learn (or be reminded) what CVAHS was up to in 2006, take a look at this video of the dig at Chesham Bois House. CVAHS members helped the Time Team crew to investigate this fascinating manor house site. Members might see their younger selves there! See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yQDJd-QZ9X0

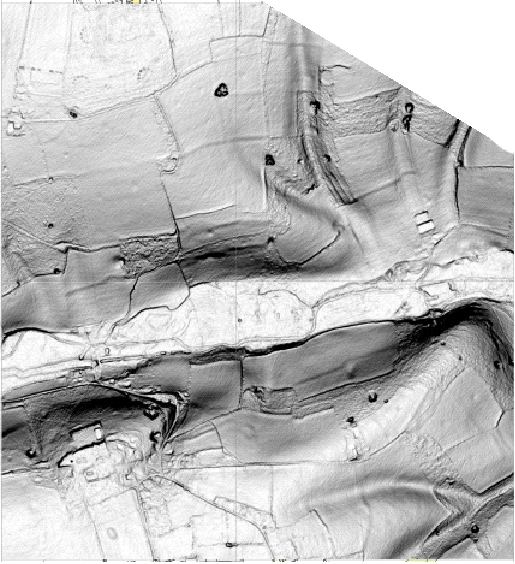

April 2022: Geophysics Survey in Little Missenden

For the first time since the start of the Covid pandemic, the Society has returned to field work. Starting on April 6th, we completed a resistivity survey over a total period of six days in Little Missenden, covering two fairly large fields. The ancient village church is known to have Roman brickwork contained in its walls and we believe that there may have been Roman buildings in the area. Our objective was to survey for such buildings or indeed any other features, pre-Roman and/or Medieval.

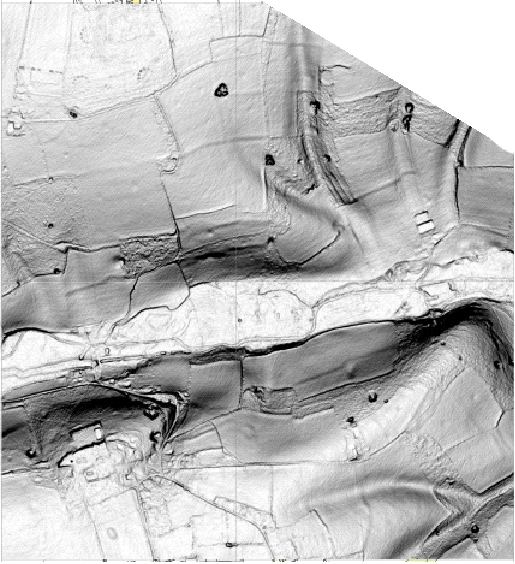

The results were encouraging. The resistivity plot below shows results from one of the fields. Towards the bottom is a rectangular anomaly some 30 by 40m and towards the top left another but incomplete rectangle. It is early days and only initial processing has been carried out, but as well as the highlighted features, there is the possibility of others present. More work needs to be done.

There was a very good response from members to the request to help on this survey. We would like to thank everyone who helped and all those who volunteered and were not able to be included. The photos show two of our members operating the resistivity meter, and a rough plot of the results showing distinct rectangular features.

April 2021: An Unexpected 'Dig' in Chalfont St Peter

Early in April CVAHS received an unusual request from a resident of Chalfont St Peter. A hole had suddenly appeared in the grass verge of his street and, upon investigation, proved to be over eight metres deep. Would CVAHS like to take a look?

Two CVAHS members took up the invitation. The resident supplied a strong floodlight, while CVAHS supplied a video camera (a GoPro HERO 3) that could be lowered down the hole,plus a telephoto stills camera. Our investigation quickly established that it was a water well, brick-lined all the way down. The size and condition of the bricks indicated that it was probably Victorian in age. The well was completely dry with a hard base, although the water table is believed to be considerably lower then 8 metres in that area. What may have happened was that the well was filled with earth and stones when it was put out of use. Over time, these would have been washed away from the bottom by water action, causing the fill to subside.

As the well is in an unadopted road, the residents are now responsible for making it safe. While we were there they were already debating the merits of filling it in versus fixing some kind of cap over the top. The situation is complicated by the fact that a concrete electricity box was sunk into the ground some 50 years ago, cutting into the top of the well. It is now largely hanging in mid-air above the drop.

Interestingly, this particular well may not be their sole problem. We consulted an OS map from the late 1800s and saw not only this well marked, but another one on a grass verge within 100 yards. When we went to look for the latter, we quickly spotted a round depression in the grass just where the well was marked on the old map. The owner of the adjoining property has been warned and has promised not to jump on that spot!

The photos show: lowering the video camera into the well, while the local resident watches on a hand-held screen; a floodlit view of the well; close-up of the brick lining.

And if any of this has whetted your appetite for wells, take a look at the amazing story of the deepest hand-dug well in the world. It’s British and it’s 1280 feet deep! https://www.mybrightonandhove.org.uk/places/utilities/woodingdean-well/woodingdean-well

October 2020: A Test Dig in Old Chesham

One of the frustrations of us amateur archaeologists during the current pandemic is the lack of digs to get stuck into. But some CVAHS members are finding an alternative – digging test pits in gardens. Done by just one or two people (suitably distanced) these can throw up some interesting results.

Most recently, two CVAHS archaeologists investigated a garden in old Chesham, close to the intersection of the roads leading to Great Missenden and Amersham - a site that has probably seen human habitation for many centuries. This was amply confirmed in the first day of digging in the 90 x 120cm test pit, when the first 15cm of depth yielded a Victorian slate pencil, a sherd of medieval greyware and a prehistoric flint blade, all mixed with fragments of brick and tile.

As digging progressed, a plethora of finds emerged, ranging from relatively modern items through Victorian to mediaeval: glass, a lead pipe, a metal spike, nails, sheep bone, clinker, a second Victorian slate pencil, a broken tortoiseshell brooch, a metal cylinder of identical diameter to the slate pencils, and a bottle cap. Potsherds included garden pot, white glazed, blue and white glazed, medieval unglazed greyware, green speckle tin glaze, dark brown glazed, redware with flint inclusions, and grey stoneware with stamped incisions. All this in the first 30cm or so!

Continuing on down to about 65cm, the volume of mediaeval pottery increased, though still mixed with some modern ceramic fragments. In addition, some suspected Roman pottery shards appeared.

Finally, on day 7 after much hard work and at a depth of just over 1 metre, the two diggers decided to call it a day. But not before they had discovered near this level a Roman rim, an abraded sherd of Samian and a sherd of greyware. And, in addition, a large piece of slag with ceramic material still attached – part of the structure of a kiln. See photo of Day 7 finds below.

The presence of medieval pottery in most contexts is interesting, and that of Roman pottery in both disturbed contexts and at an alluvial level is worthy of further investigation in the form of test pits or geophysics. It is possible that there are further underlying levels of alluvial and gravel deposits below 1 metre which could provide more information about land use in Roman and pre-history contexts.

CVAHS members are preparing a full report and suggested next steps that will be published in the next few months.

This is a summary of the work at Kennel Farm, Little Missenden, briefly described in previous news items. A full report is also available as a pdf file by following the link at the end of this article.

The dry summer of 2018 resulted in a series of cropmarks becoming visible in the Misbourne Valley. One field in particular stood out at Kennel Farm immediately east of Little Missenden - see map at https://osmaps.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/51.68284,-0.65465,15 These marks consisted in the east of two straight linears joined at right angles and a further partially sinuous one to the west. There were also two rectangular features to the west. All were on the north side of the river which runs through the farm land. The village area is understood to contain a Roman settlement and was the site of at least two watermills. In the late 19th C three known water cress farms were in operation, one of which lay immediately east of the field of interest.

In 2019 an investigation of the field commenced with a series of geophysical surveys consisting of resistivity, gradiometry (magnetometry) and ground penetrating radar (GPR). The resistivity survey covered the whole of the bottom section of the field and was extended to the south of the river. This survey defined all of the cropmarks seen in 2018. However no features were encountered on the south side of the river. A more restricted area GRP survey was completed over the linear marks in the east and the two rectangular structures and both sets were identified. The gradiometry survey covered the same ground as the resistivity but only the sinuous cropmark in the west gave any response. Surprisingly this survey identified an unexpected and unknown buried pipeline to the south of the river.

These surveys were followed by excavation of three trenches each initially 1m by 5m. Two covered the eastern linear cropmarks and the third one of the rectangles. Trench 1 was the most eastern. In its south western end excavation exposed various river gravels with no sign of human activity, but towards the centre encountered a low mound/bank of clay which aligned with the cropmark. Abutted against this on its north east side were two vertical wooden stakes. The north eastern area was very different as beneath the subsoil was a 12cm thick chalk layer extending beyond the trench limits. Further deepening beneath the chalk led to an area of disarticulated horse bones and one pig skull. These were contained in a shallow ditch parallel to the clay bank. The bone layer was carefully recorded. There were no additional finds beneath these bones and the excavation was terminated. One bone and a stake were collected for future radiocarbon dating.

Trench 2 was placed some 30m to the north west on the conjoining cropmark. In the southern zone of the trench river gravels dominated with no indication of artefacts. Again the northern trench area was different. Immediately beneath the subsoil was a sticky clay containing numerous broken peg tiles interspersed with burnt flints and blackened soil. These two parts of the trench were separated by a zone of grey clay which overlay gravels but this time no sign of this material forming a mound or bank. This northern clay margin had a large vertical stake set into it with its base in standing water. Further excavation revealed a large horizontal beam crossing the trench but this could not be examined further as it lay beneath the present water table. Part of the stake was chosen for later radiocarbon dating.

Trench 3 was positioned to cover part of one of the rectangular cropmarks. In general the subsurface contained loam with small flints, but in the centre there was a shallow clay filled ditch with a near complete late 17th C clay pipe embedded in it. Beneath the clay were two possible small post holes. Further deepening resulted in a gravel layer and it was concluded that the natural river bed had been reached.

We are still uncertain as to the origins of the features in trenches 1 and 2. Roman period activity is very unlikely and there is nothing to support mill workings. At this stage interpretation leans towards association with the commercial watercress farms. The future radiocarbon analyses should pin down possible dates, but we are prepared for surprises. The trench 3 area is different and not related to watercress features. We do at least have the clay pipe which ties it in part to the early modern period. As to the function of these rectangular cropmarks, which appear defined by shallow ditches, we do not know at this stage. We await the radiocarbon dates for further clarification.

We would like to thank David Brazzard for his kind permission to work on his land.

A more detailed report can be found by following this link (pdf version)

October 2019: Further Work at Little Missenden

In the autumn of 2019, CVAHS continued investigating a site alongside the River Misbourne at Little Missenden, following on from surveys in April. Initially, we worked over three days using a magnetometer, an earth-resistance meter, ground penetrating radar and a drone aerial photogrammetry data set. These activities revealed geophysical features of interest, and trenches were positioned to investigate three of them. In the course of excavation, there were a few surprises.

For example, Trench 1 yielded an unusual block of solid grey clay in its central area. This clay may have formed a small bank next to a possible ditch at the north-west end of the trench, into which a large number of horse bones had been placed, at some point covered by a thick capping of chalk. This chalk layer appeared as a roughly rectangular area in the geophysics.

In Trench 2 we exposed various features including an area of burning. At the same depth there was a large amount of broken roof tile (peg tile) and a near vertical timber. The water table was about 20cm below the top of the timber. However, the timber was extracted and was over 1.4m long with most of its length under the water table. There was another larger horizontal timber adjacent to the upright, which was visible under the water, but this was left in place.

Trench 3 revealed a central cross-ditch at the lowest level which was the feature identified by the geophysics. This trench also produced the only dateable find from the field which was an almost complete clay tobacco pipe. Later research discovered that this style of pipe was used about 1700. Further work is needed to determine the significance (if any) of these discoveries.

April 2019: Little Missenden Survey

Members of CVAHS have spent some time looking at possible sites for further research and excavation. One such site is in a field near Little Missenden, where John Gover had noticed an interesting rectangular feature. We tracked down the friendly owner who readily agreed to CVAHS surveying the site.

On the 23rd of April we set to work. After an initial walk over the field, the geophysics grids were laid out and surveyed. By the end of the first day they had identified a possible linear feature close to the river. Work continued on subsequent days, revealing additional features such as a number of raised bumps. The results are now being analysed with a view to another survey (magnetometry this time), and then a dig if the site looks promising.

CVAHS took advantage of the long hot summer this year. We used our drone to take aerial photos of the Chess and Misbourne valleys, looking for parch marks on the ground. These parch marks occur where grass, or other ground cover, dries out more quickly over buried walls and paths, revealing the underlying forms. Alternatively, the grass may appear greener over buried ditches, land drains and the like.

Numerous large markings appeared over the course of the summer, some of which show promise for further investigation. A selection are shown below: rectangular marks by river; rectangle with interior marks; large parched rectangular area.

However, the second photo is actually the pitch at Little Missenden cricket club, so one has to be careful interpreting marks!

February 2018: Medieval Excavation at Frith Hill

After over a year of pursuing an application, in early 2018 CVAHS was finally given the go-ahead by Historic England for a dig at Frith Hill. The site has the clear remains of a bank and ditch structure on a hill overlooking Great Missenden. Historic England describes it as a moated site likely dating from 1250-1350 which is the peak period for such medieval sites. Our dig uncovered large volumes of pottery which appear to match these dates.

Various people who explored the site in previous years proposed that it may have been an ‘adulterine’ castle (a fortification built without royal approval), possibly erected by Hugh de Noers, but as yet we have no direct evidence for this. Hugh de Noers was a supporter of King Stephen during 1135-1154 when he claimed the throne against the rights of his cousin Matilda. The de Noers family provided grants for the building of Missenden Abbey (c. 400 metres to the SW) in 1133.

We were granted permission for limited excavations, including three trenches, 1m wide and 4m long, crossing the upper and lower ditches and another across the uppermost platform.

Trench 3: excavation across the lower ditch revealed that this was originally about 2.2m deep below the upper bank – a formidable barrier. We found some slag with pot and bone fragments in the topmost layers. Below this, about 1.2m down, a black soil deposit yielded finds of blackened pot fragments and animal bone. The lower levels contained very few finds.

Trench 2: excavation of the top platform nearest the road revealed it to be a dump of 20th C building material and other rubbish, probably tipped out of a passing lorry!

Trench 1: this trench across the upper ditch was the most productive in terms of finds. Below the topsoil, we encountered an area of large stones, loosely packed and interspersed with large numbers of early pot fragments. This area was from 25cm to 85cm in depth and included many fragments of considerable size. Several came from the same pots, enabling subsequent partial reconstructions of large vessels. Early examination of the pottery suggests these are likely to date from the 12th to 13th C.

Overall, a very productive dig, and we hope to obtain permission for further investigation in the future.

The pictures below show: a general view of the site from the top platform; happy diggers in productive trench 1; a large jar undergoing trial reassembly.

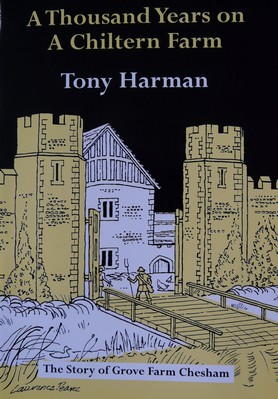

October 2017: Visit to Grove Farm

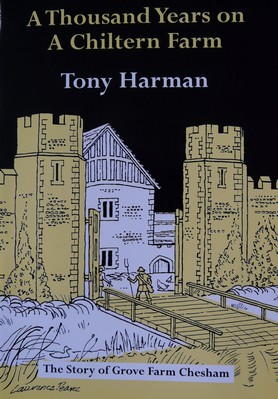

In early October, seven members of CVAHS took up an invitation from Madeleine and Dan Harman to visit their home, Grove Farm near Chesham.

The farm has a very long history, as recorded in ‘A Thousand Years on a Chilterns Farm’, a booklet by Dan’s late father Tony Harman. It was also the subject of a geophysical survey by CVAHS back in 1999 and a description of this appeared in The Journal of 2001. Copies can be ordered through ‘Publications’ on this web site.

Grove Farm is still a working farm, centred round a restored house dating back to at least 1500. The most striking feature of the property is the enormous moat that surrounds the house, and CVAHS members spent a happy hour walking around examining it, and also the remains of two octagonal towers and a defensive wall on the inside of the moat.

The moat is truly impressive – as much as 70ft wide and 18ft deep in places – with standing water in some sections. It forms a rough square and, including its outer banks, encloses an area of about seven acres . It seems appropriate for a pretty large castle, but no such structure ever stood here as far as is known.

One theory is that the moat may have originally been an Iron Age bank and ditch enclosure that was adopted and adapted to its new use in medieval times. Certainly, Romano-British pottery has been recovered from the base of the moat, which suggests an early date.

An enjoyable morning was rounded off with chat over coffee and cakes kindly provided by Madeleine. Our thanks go to Madeleine and Dan for hosting this very interesting visit.

Photos below show: Tony Harman's booklet with an artist's impression of the entrance to the fortified house in about 1500; the same view today; Yvonne and Phil inspecting a section of the surrounding wall; a dry section of the moat.

September 2017: Back to the Bottom

Continuing a tradition dating back several years now, CVAHS once again surveyed and dug at Sarratt Bottom.

This time, in September, we were investigating an area near the watercress farm with the enthusiastic support of the farm owner. The work consisted of a geophysical survey of a new field and also a re-excavation of an area where we discovered Romano-British remains a few years ago.

The new field revealed few features in the survey results, apart from one area that John Gover recognised from his Lidar images as a possible banked area. We may explore this with a small-scale excavation later in 2017.

We also took the opportunity to further explore the end of the field that we looked at in 2012. At that time the excavation yielded about 40 fragments of Romano-British pot and tile. This time our excavation of a trench dug parallel to the 2012 trench has yielded significant numbers pot and tile pieces, and also animal bones. These were at a depth of about 60cm.

Shortly after this level we reached the water table and digging was ended. Birgitta and Rhian did much of the excavation and also cleaned and prepared the finds. The photos below show Birgitta and Rhian reenacting the Somme trenches: finds of Romano-British pot and tile; oyster shell from a Romano-British meal.

May 2017: Investigating a Surprising Garden Feature in Sarratt

CVAHS received an interesting email in May from a resident of Sarratt village. While remodelling his garden, the owner had found a large brick-lined hole under a paved area, accessed by a manhole-sized entrance. The circular hole was about 3 metres deep to debris deposits at the bottom, and 2 metres wide. Was it a well, an ice-house, or what? The owner's house had been built in the 1950s, but on land previously occupied by a manor house, possibly in its orchard area.

Yvonne Edwards and Phil Nixon agreed to investigate. After some consideration, and climbing down into the hole for a closer inspection, Yvonne concluded that it was a cistern for storing rainwater, probably at least 100 years old. There are two inlets in the walls of the hole, but no indication of where the water source may have been. Could it have been used for watering the manor house garden or glasshouses in the summer?

The interior brick walls have been coated over with a strange grey 'paint', perhaps to aid waterproofing. The cistern has been used in more recent times to dump bottles, window panes and other debris, all of which is now coated in a grey chalky substance.

Do YOU have any features in your garden that may be of archaeological interest? If so, CVAHS would be pleased to investigate!

The three photos below show the opening to the cistern as discovered; Yvonne bravely descending into the depths; debris at the bottom of the cistern and the painted wall.

.

February 2017: Exploring the Past at Missenden Abbey

A small team of CVAHS members have been revisiting the archaeological investigation of Missenden Abbey. This was originally led by Peter Yeoman for Bucks County Museum in 1983-1985 when further buildings were planned in the Abbey grounds. At that time excavation revealed numerous remains of early archaeological features dating from the 11th to 16th C and beyond. Although much basic information was secured and a few specialist reports prepared, lack of funds prohibited completion of this important study. CVAHS recovered the archive from the Resource Centre at Halton and undertook to review, complete and publish this work, so that the early life of this important, but little known, medieval abbey will now be accessible to everyone.

During the past few years we have worked on all of the areas not recorded previously and improved those where information was minimal. All of the text is now written up and completed, the non-text data are also assembled, together with drawings prepared in the past and many new additions have also been made. We are planning to submit the complete document in the next month or so.

Meanwhile, to give you a small flavour of the finds made in the 1980’s and in the recent CVAHS studies, a few photographs are shown below. One is of Peter Yeoman and his team are relaxing at lunch time (love the hats!). Another is of architectural stone finds, some of which is on view in the present day Missenden Abbey. Our new study has investigated these in more detail. Finally, we show a few of the many Penn tiles that were found both in the early Abbey and the nearby St Peter and Paul church (it seems likely that some of these were moved from the abbey to the church at the dissolution).

.

June 2016: Resistivity Survey at Sarratt Bottom

At the end of June we carried out a resistivity survey at Sarratt Bottom on land belonging to the Watercress Farm. The objective was to look for evidence of Romano-British buildings, as we have previously found traces of such buildings in the fields of adjacent Valley Farm.

We were not expecting great results as the survey site is now unused scrubland that contains a number of small pits resulting from gravel extraction in the past. The weather was generally fine, and we completed a total of eleven 20m by 20m grids.

As expected, the results were variable, with the gravel extraction areas clearly standing out. However there was one zone with possible signs of a building. To investigate further, we plan to extend the survey slightly with two additional grids adjacent to this zone.

Many thanks to all who helped make the survey a success.

February 2016: Common Wood Excavations

CVAHS members made an early start to the 2016 digging season with a two-week spell in Common Wood near Penn during February. The dig was advertised by posters in the wood and we were joined in our efforts by a number of keen local residents.

CVAHS member John Gover made initial investigations of the wood in 2015 using publicly available Lidar data. This aerial survey revealed a significant structure lying to the eastern side of a known Romano-British earthwork excavated by CVAHS in 2005-6. It was this extension that we excavated in February.

Although the banks and ditches of these new earthworks were less prominent than those of our earlier earthwork, they were still clearly visible on the ground. We dug three long trenches across various points of the bank and ditch, and another across an associated large, shallow depression. Excavation showed that the ditches were not particularly deep, in fact we reached a solid clay surface level at their centres within about half a metre. The shallow depression yielded no information.

The most obvious finds from the trenches and the general surrounding area were numerous pieces of slag, some of which were 10cm across. Much slag was also found in our previous dig in 2005-6, confirming that this was an area of extensive metalworking.

A separate rectangular bank lay between the ‘extension’ described above and the previously identified Romano-British earthwork. The layout here was suggestive of a possible wall base, but excavation revealed only a shallow blackened surface followed by solid clay surface at 12cm depth.

During the final three days of the excavation, we took the opportunity to further explore the original Romano-British site and to place trenches across the inner ditch in two separate areas. Both trenches uncovered quantities of Romano-British pottery at the 40-60 cm level. The pottery is currently being examined and identified.

July 2015: LIDAR in the Woods

CVAHS have been working hard on the assembly of the LIDAR data for Penn Wood and this is now almost complete. A number of interesting features have been identified including a rectangular bank and ditch enclosure, about 90metres square, with various linear ditches nearby. Numerous other banks and quarries have also been located in the wood.

We aim to organise a walk for members to take a look at some of these features and this may be best done in the late winter/early spring when there is little foliage to contend with. Recent walks around Penn Wood and research into its history has shown that the planting and replanting of trees in the past 200 years has probably destroyed many early man-made surface features, so these remaining features are of particular interest.

We have also extended the LIDAR survey to cover parts of Common Wood, including the Romano-British enclosure investigated by CVAHS in 2005. Remarkably, this has revealed further structures that appear to be extensions to the enclosure.

Next year, it may be possible for CVAHS members to survey and excavate both the Penn Wood enclosure and these additions to the Common Wood enclosure.

June 2015: Trial Trenches in Latimer Field

In early June, CVAHS carried out trial trench excavations at Latimer, not far from the original Roman Villa site. This work was to follow up on last year’s resistivity surveys, that had highlighted a number of features worthy of investigation.

Over the course of a week, five exploratory trenches were dug, all of which encountered scattered finds of 17th- 19th C fragments of tile, pot, glass and pipe stems in the upper layers. One of the Trenches (No 3) showed three parallel linear features cutting across the trench at a depth of c. 30-35cms. The size and shape of these grooves suggested that they marked the occasional traverse of a cart, whose wheels sunk into soft ground.

Two of the trenches (No 2 and No 5) yielded good numbers of fragmented Roman finds at lower levels (40-55 cms depth). The finds included fragments of tegulae, tiles, box flue tile and various domestic items.

In order to establish whether the finds were associated with a constructed feature, such as a wall, pit or trench, Trench 2 was doubled in size but no evidence of man made features was found. It appears that Trench 2, and perhaps also Trench 5, uncovered dumping areas from the Roman period. More details on the excavation and finds will appear in this year’s CVAHS Journal.

In May, CVAHS members were busy once again at the Whelpley Hill site, where we conducted surveys and digs in 2013 and 2014.

This probable Iron Age site has already revealed several interesting features. In Spring 2014, we excavated a linear trench across one of the four identical circular, high resistance, features located on the east side of the Whelpley Hill enclosure. The excavation team uncovered several surface levels, the uppermost of which were cut by what were apparently ploughing grooves. At lower levels we encountered clusters of small postholes and two larger holes, each surrounded by closely packed stone. The large holes may have been cut to support roof posts while the small postholes may mark the site of structures for drying and preserving food, a feature of life from the Mesolithic to the Iron Age.

During May this year we extended this trench to the south in the hope of uncovering further features associated with this circular structure. Not surprisingly extensions of the ploughing grooves were uncovered. Further down, more groups of small postholes, the positioning of which varied between levels appeared, perhaps associated with changes in the hut interior over time. In addition, at the deepest levels a number of interesting larger features were uncovered, including two apparently contemporary, short ditches at the west end, running across the trench. Both features were marked by stone edging and were filled with greyish crumbly clay. At the east end, a ditch about 60cm wide and a with maximum depth of about 30cm was uncovered. This feature crossed the trench from south to north, diminishing in width towards the north.

We plan to combine the data from the 2014 and 2015 trenches, level by level; this should provide an overview of a good portion of this circular structure. Charcoal was recovered from a number of features, some of which is suitable for radiocarbon dating. Now we need to raise funding for this!

An admirable team of diggers worked for the ten days of the excavation, including our president Stan Cauvain who trowelled away and also gave us some very good advice.

Many of you will already know that a CVAHS team have been working on the unpublished data, finds and maps etc., from excavations at Missenden Abbey which took place in the late 1980’s. The work is well underway and almost complete. We are planning to publish the fascinating history of the Abbey and the wealth of excavation findings; such an important volume will add considerably to knowledge of the Chiltern area.

We will need to attract funding in order to publish the Missenden Abbey Book. As it happens the Institute of Archaeology at UCL asked if they could use this work, along with two other projects, to test their first foray into an on-line "crowd–funding" project. This can be viewed on the "MicroPasts" website https://crowdfunded.micropasts.org/

It would of course be excellent if you could make a contribution, however small, to the fund. The project will be on-line for contributions until the end of 2014, so please act soon. If you would prefer to make a donation without going on-line please send to CVAHS c/o M. Wells, Holly Bank, 36 Botley Road, Chesham, Bucks HP5 1XG.

For further information on this new venture in archaeological funding, there is an article about Micropasts, including a description of our project, in the November/December 2014 edition of British Archaeology magazine.

In July, CVAHS was fortunate to have the use of a wheeled Foerster gradiometer to survey fields at Latimer and Sarratt Bottom, both of which are potential Romano-British sites. The gradiometer is priced at about £40,000 – far out of our league – but has been funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council for a project run by UCL.

The project is directed by Kris Lockyear, Ph.D, Senior Lecturer at the Institute of Archaeology at UCL, who helped us with the surveys (that's him above, adjusting the gradiometer). The project’s aim is to conduct archaeological magnetometry surveys on a number of Late Iron Age and Roman sites throughout Hertfordshire, in collaboration with local heritage and archaeological groups such as CVAHS.

Two happy days were spent in the sun by a total of about twelve CVAHS members and we are now analysing the results to see if they show features that merit further investigation.

For more information about the UCL-run project, see www.hertsgeosurvey.wordpress.com

CVAHS is taking another step into the latest archaeology techniques with the use of LIDAR surveys of the Chess Valley. LIDAR uses laser beams fired from a plane or helicopter to map the terrain beneath, and the results can be filtered to remove vegetation and reveal hidden features.

We cannot yet afford an aircraft to conduct surveys, but fortunately the Environment Agency has already carried out airborne surveys along the Chess and Misbourne Valleys for flood control and has made the data freely available to non-commercial bodies (see https://www.geomatics-group.co.uk/GeoCMS/Order.aspx ).

We have downloaded a portion of this data in the Chenies and Valley Farm area of Sarratt Bottom and are in the process of interpreting this for its archaeological potential. The picture below shows the LIDAR image of this area with most vegetation removed and with vertical contours exaggerated. The River Chess flows through the pale strip that runs horizontally across the plot. Several interesting features are revealed, including various circular and rectangular structures, and possible field terracing.

Our next step is more traditional archaeology, using maps and field walking to investigate these features on the ground. For instance, towards the top of this LIDAR projection are some dotted ring structures. Are these hut circles or long lost prehistoric henges? The answer lies in the ordnance survey map; they are the foundations of modern radio masts!

We intend to extend our LIDAR coverage in the near future to identify areas for investigation and possible digs.

More about LIDAR. The principle behind LIDAR is really quite simple. Shine a small light at a surface and measure the time it takes to return to its source. The LIDAR system pulses a laser beam onto a mirror and projects it downward from an airborne platform, usually a fixed-wing airplane. When the laser beam hits an object it is reflected back to the mirror. The time interval between the pulse leaving the airborne platform and its return to the LIDAR sensor is measured. This is done many thousands of times a second. The data is post-processed and the LIDAR time-interval measurements from the pulse being sent to the return pulse being received are converted to distance.

LIDAR is extremely useful as by special filtering it is possible to penetrate the beam through vegetation such as woods and forests. This allows the ability to measure the height of the ground surface and other features in large landscape areas with a resolution and accuracy hitherto generally unavailable. It provides, for the first time, highly detailed and accurate models of the land surface at metre and sub-metre resolution

As some members may recall, CVAHS Field Group found a Romano-British intaglio stone from a signet ring during our 2008 excavation at Valley Farm. The blue stone contains a carved figure and was found in a trench where two Trajan sestertii were excavated.

A PhD student at Leicester University recently contacted us about this intaglio after he saw an account of it on our web site. He is currently trying to locate all such finds from Britain as part of his doctoral research. One of the aims of this research is to map the popularity of various deities across Roman Britain, as reflected in their presence on intaglios. He describes our intaglio as being made of glass paste and the figure appears to be an image of Sol. When viewed in impression, he is standing facing the left with his 'lucky' right hand raised in a gesture of welcome.

Sol, or Sol Invictus ("Unconquered Sun"), was the official sun god of the later Roman Empire and a patron of soldiers. In 274 the Roman emperor Aurelian made Sol an official cult alongside the traditional Roman cults. Sol is fairly uncommon on Romano-British intaglios, especially on those from rural sites. Although it was found with coins of Trajan, it probably dates to the late second-century or early third-century, based on its fairly crude moulding and its similarity to other known third-century examples.

CVAHS Field Group is taking to the skies. At our recent Whelpley Hill dig we were able to see the whole site and individual trenches from above, thanks to a ‘flying eye’ introduced by CVAHS member and professional cameraman Phil Nixon.

Phil’s machine is a DJI Phantom Quadcopter, so-called because it has four rotor blades. It can carry a camera capable of taking digital stills and video, yet measures only 330cm square and can fly for up to 12 minutes on one battery charge.

In operation at Whelpley Hill, the Phantom hovered just 10 feet above individual trenches, but soared hundreds of feet into the air for a shot of the whole site. And despite the strong wind that blew for most of the dig, the Phantom could remain stationary over a particular spot because of its in-built GPS and autopilot system.

We expect the quadcopter to become a feature of future digs, and also perhaps assist in spotting crop marks and other features indicating hidden archaeology.